Bridges Through Literature

Dear Friends,

Welcome to May’s Substack.

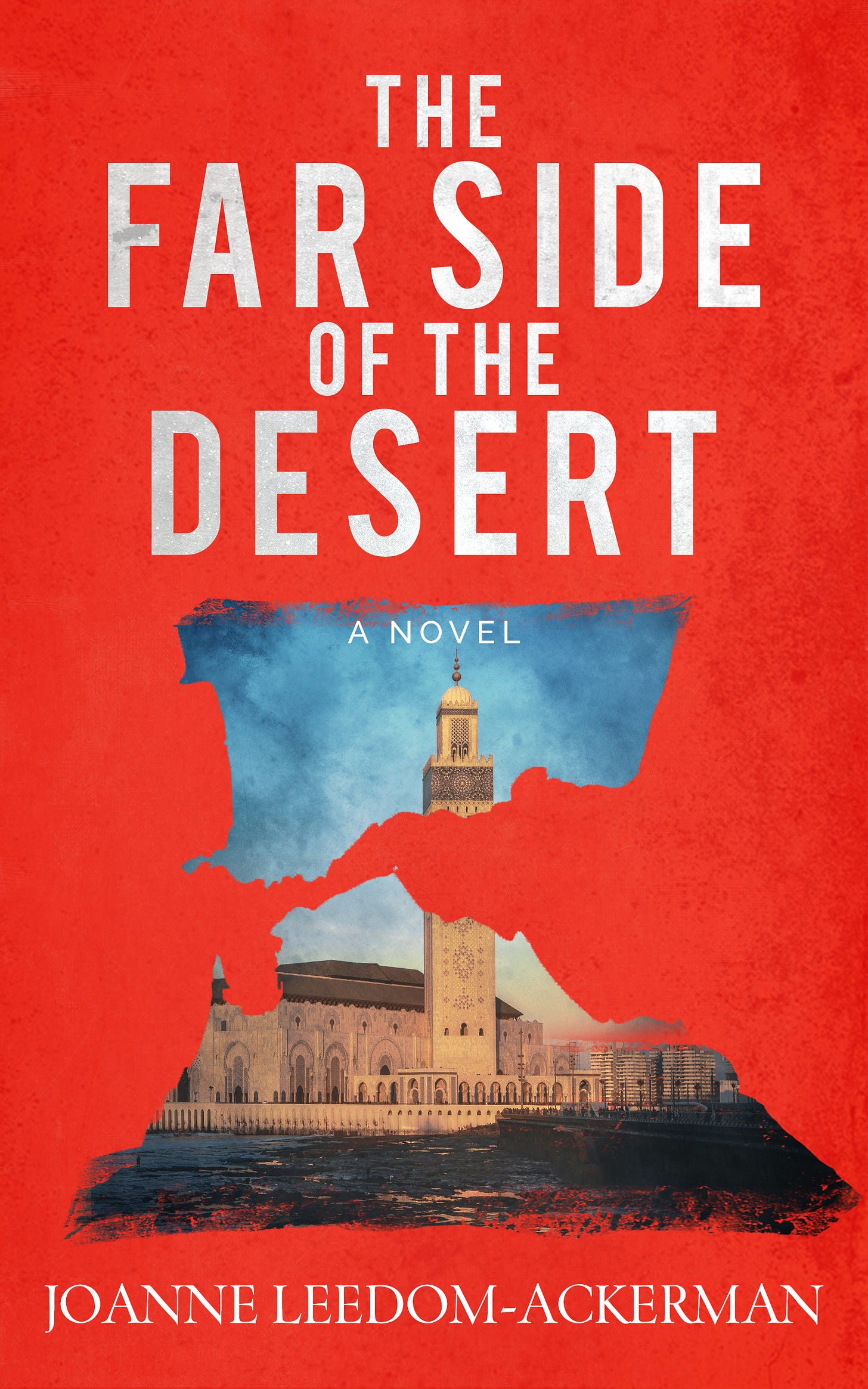

Since publication of my novels The Far Side of the Desert and Burning Distance, I’ve met old friends and new readers in bookstores, book clubs and online venues and look forward to future events. An events calendar is below. If you’re engaged by the novels, thank you for telling your friends and leaving a review with an online bookseller. Reviews help spread the word!

In my blog this month— Bridges Through Literature— I consider the role of the writer in a fraught political time. “As writers we have the luxury and the responsibility to look deeper into the human spirit to find what binds us, to see bridges where others only see chasms.”

The Writer at Risk section focuses on the case of Gui Minhai, a Chinese-Swedish writer, publisher and bookseller, abducted twice by Chinese authorities and now sentenced to ten years in prison.

In Books to Check Out are paired two novels through interconnected short stories, one by an emerging Palestinian writer Susan Muaddi Darraj whose book Behind You Is the Sea shares the stories of multi-generational Palestinian families in Baltimore with all the joy and heartache of families in a new land and Amos Oz’s Between Friends which shares the stories of families in a 1950s kibbutz with the idealism of past and present at play and in conflict.

In the Scene section you’ll find a new photo of a setting, along with text from The Far Side of the Desert, located in Santiago de Compostela, a setting in the blog.

I hope you enjoy these and other features and share this monthly Substack with friends. Subscribe if you haven’t already. On the Yellow Brick Road Substack is free!

I love a good audiobook and am glad to share an excerpt from my new novel, The Far Side of the Desert, narrated beautifully by Robin McAlpine. Enjoy and head over to Audible or Apple Books to download the entire audiobook. Click the image below to hear the opening pages.

Pleased to see The Far Side of the Desert included in Bookreporter’s Summer Reading. You can sign up for their daily contest to win a copy and check out all the books on their list. Happy summer reading!

I’m honored to have The Far Side of the Desert (Oceanview Publishing) included among The 10 best new books of March 2024 by The Christian Science Monitor.

The Far Side of the Desert, by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Alliances – familial, situational, political – gird this engrossing thriller from novelist Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. U.S. foreign service officer Monte disappears during a visit to Spain; the search to find her, spearheaded by older sister Samantha, ricochets from Morocco and Egypt to Washington. Monte’s captivity is brutal, but there’s resilience, too, as both sisters slay old demons and chart new paths.

—The Christian Science Monitor

“The Far Side of the Desert is a riveting thriller with richly nuanced characters and fast-paced action. The plot imaginatively taps into recent history to illustrate the human dimensions of terrorism—both the complex psyche of the perpetrators and the gnawing questions among those sucked into their vortex. I binged until the end.”

—Robin Wright, author of Rock the Casbah: Rage and Rebellion across the Islamic World

Selected recordings of events and interviews include:

Malaprop’s Bookstore and Café in Asheville, NC

Kinokuniya Bookstore in New York City with Salil Tripathi

Baum on Books on WSHU Public Radio

Interview with Anna Roins of Authorlink

Interview with Deborah Kalb

For more podcasts, videos and interviews, click here.

My novel Burning Distance (Oceanview Publishing, 2023 and recent paperback in 2024) was honored by Reader Views with a Silver Award in the Thriller/Suspense category.

“Burning Distance opens with a mystery, glides into a love story, and unfolds into a political thriller. Set against the backdrop of 1980s and 90s global politics, readers will be up way past their bedtimes eagerly turning pages to discover what happens to Lizzy and Adil. A story of war, family, history, politics, and passion. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’s evocation of the era is pitch-perfect. A great read!”

—Susan Isaacs, New York Times best-selling author of It Takes One To Know One

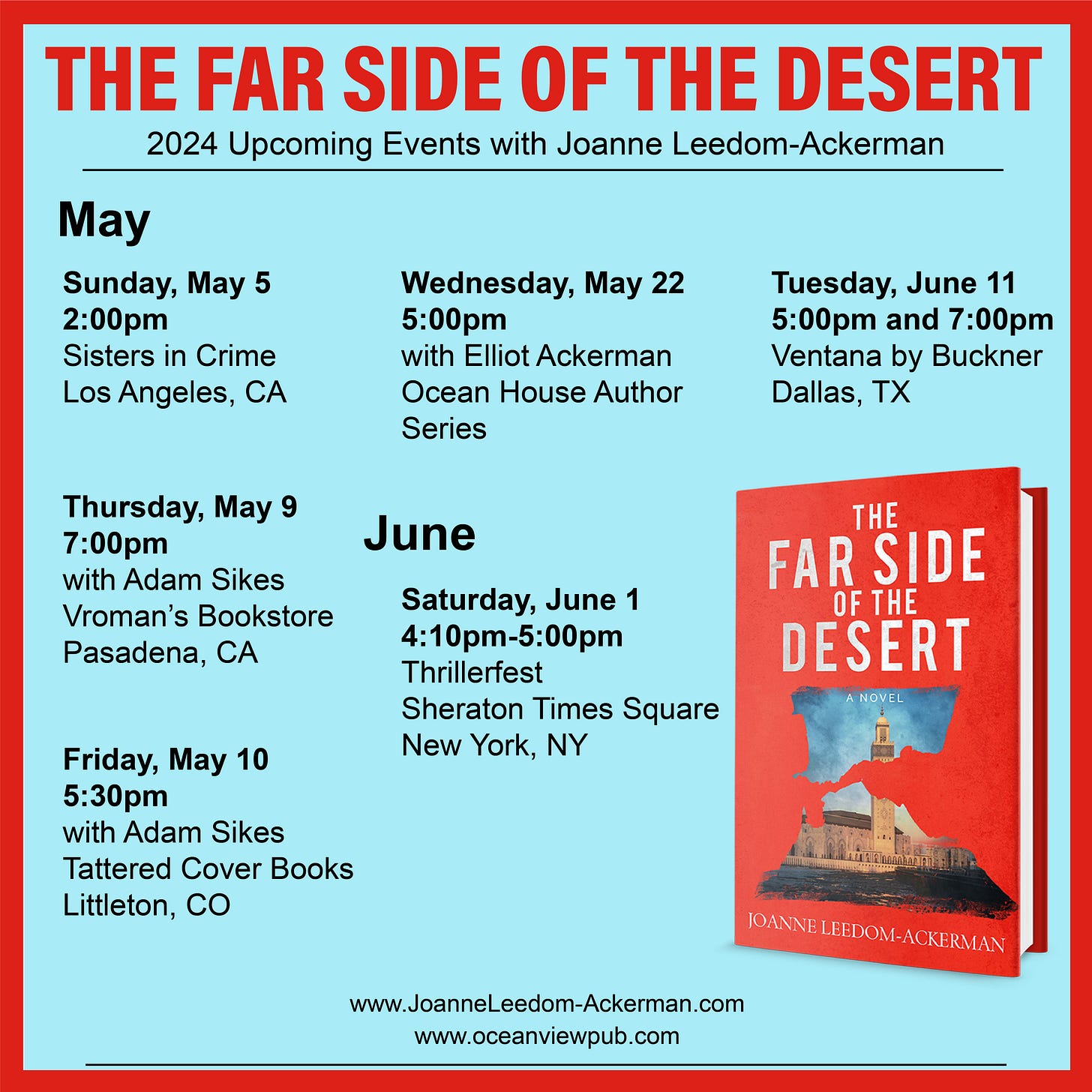

Below is a May/June calendar of events for The Far Side of the Desert. More events will be added and details for the events below and for past events can be found on the Speaking page of my website.

Thank you to all who came together and shared the March and April readings and conversations.

Bridges Through Literature

In the early years of this century—2004-2007—I was elected the International Secretary of PEN International, a position at the time responsible for overseeing the running of the day-to-day operations of the global organization, along with a small staff. (During my term we hired the first paid executive director.) PEN’s international organization includes four standing committees—the Peace Committee, the Writers in Prison Committee, the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Women Writers Committee.

Because I’d been Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, which oversees the human rights activities of PEN and takes action in defense of writers in prison and at risk around the world, I understood this committee’s work and mandate. I understood the work and mandate of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee to defend minority languages and promote the translation of literature globally. And as one of the founding members of the Women Writers Committee which opened up representation by women in PEN and globally, I understood its mandate.

But the Peace Committee always seemed to me more ethereal and abstract. As writers we were not usually at the peace tables, though unfortunately at that time certain writers in the Balkans had helped foment the conflict. Besides passing resolutions for peace and hosting symposiums, what actions could the committee take? One idea of mine, which never did operationalize, was that writers on opposite sides of a conflict could read each other’s best work—not political or polemical work—but the best literature which deals with the human heart and aspirations.

What if Palestinian PEN chose one of the best writings by a Palestinian writer and Israeli PEN read and discussed it, and Israeli PEN suggested a book by one of its best writers and the Palestinian PEN members read and discussed it? Would that open corridors of thought and conversation?

I concede now the rather naive and utopian concept, but to move this utopian vision further into the clouds, what if the members of the two centers could meet and discuss the works as fellow writers! Well, not all dreams come true. Especially when formulated by someone outside of the conflict zone and insulated from the intense emotions and realities on the ground. I admit idealism is not always helpful.

But PEN is an organization of writers, not of politicians or military strategists. As writers we have the luxury and the responsibility to look deeper into the human spirit to find what binds us, to see bridges where others only see chasms.

At the height of the war in the Balkans in 1993, PEN International held its 60th global Congress in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, where the presidency of the organization passed hands from Hungarian novelist György Konrád to British playwright Ronald Harwood. The Balkans War was in full conflict then. Salman Rushdie visited that Congress. At that Congress I was elected Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee which brought me into the center of discussions. At the Congress a new Bosnian Center whose members were Serb, Croat and Bosnian was unanimously welcomed as was an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers who no longer lived in the region.

The 60th PEN Congress was a watershed of sorts. Konrád’s address at the opening session went a way in bringing the delegates together. “What we can do is to try and ensure the survival of the spirit of dialogue between the writers of the communities that now confront each other….International PEN stands for universalism and individualism, an insistence on a conversation between literatures that rises above differences of race, nation, creed or class, for that lack of prejudice which allows writers to read writers without identifying them with a community…

“Ours is an optimistic hypothesis: we believe that we can understand each other and that we can come to an understanding in many respects. The existence of communication between nations, and the operation of International PEN confirm this hypothesis…PEN defends the freedom of writers all over the world, that is its essence.”

Ronald Harwood added in his acceptance for the presidency: “The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a Congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t represent governments; we represent ourselves and our Centers…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough…And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

These words echo today. Linked here is the fuller account of the 60th Congress, of Rushdie’s visit and of PEN’s wrestling with the issues of the time. In PEN Journeys: Memoir of Literature on the Line is an expanded narrative of at least a third of PEN’s century which I’ve had the privilege of participating in—of its history, of writers’ wisdom, of failed idealism and also achieved visions.

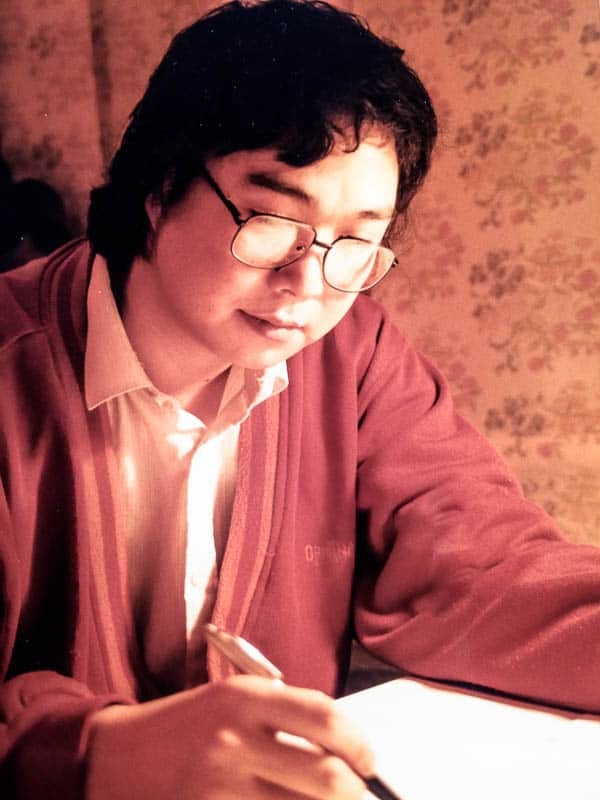

Gui Minhai (China)

(Sources include PEN International, PEN America, Reporters Without Borders [RSF], The Washington Post, BBC)

In 2015 Gui Minhai, a Hong Kong-Swedish writer, book publisher and bookstore owner disappeared, abducted from his vacation home in Thailand. Co-owner of Causeway Bay Books in Hong Kong and the Mighty Current publishing house which published books about the private lives of Chinese officials, Gui and four other booksellers became known in the the Causeway Bay Books disappearances, an early warning of the collapse of the “one country, two systems” policy between mainland China and Hong Kong as renditions from Hong Kong and other countries escalated.

Briefly released in 2017, Gui was again seized in 2018 en route to a medical exam in Beijing. According to the Washington Post, “He was riding a train from Shanghai to Beijing in the company of two Swedish diplomats when 10 Chinese plainclothesmen stormed aboard, lifted him up and carried him off the train and out of sight.”

In February 2020 Gui was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment for "illegally providing intelligence overseas" and five years’ deprivation of “political rights.” He has been charged with having distributed books not approved by China's press and publication authority.

His daughter Angela reportedly said, “He was very shaken by this. He told me, ‘I’m not afraid to die, I’m just not ready yet. There’s so much more to be done.’”

Angela Gui noted, “It is obvious that my father was arrested for one and only reason: his politically sensitive activities as a publisher.”

Gui has been pressured to confess on television and to give up his Swedish citizenship.

Also known as Michael Gui, author of dozens of books under the pen-name Ah Hai (阿海), Gui is a a novelist and poet and former board member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC).

In prison Gui began writing poetry. One of his poems is below, along with excerpts from four other imprisoned writers featured in PEN International’s March focus on World Poetry Day: Maksim Znak (Belarus), Galal El-Behairy (Egypt), Freddy Antonio Quezada (Nicaragua) and 12 Eritrean writers detained since 2001.

(On the Yellow Brick Road January’s Substack featured a profile of Galal El-Bhairy.)

Poetry:

By Maksim Znak (Belarus, imprisoned; held incommunicado since February 2023)

They considered us totally buried.

But how can one just bury a plant?

Our greens broke persistent through bedrock, And the blue sky we finally found!

By Amanuel Asrat (Eritrea, held incommunicado for 22 years)

The ugliness of this thing, war; When its spring arrives unwished-for; When its ravaging echoes knock at your door; It is then that war’s curse brews doom.

By Galal El-Behairy (Egypt Imprisoned; held in arbitrary detention since July 2021 after serving a three-year prison sentence for his poetry)

Against 1912 nights in which I only saw the moon once, and by chance

Against every dream that dies over time and joins all my wasted dreams.

By Freddy Antonio Quezada (Nicaragua, Detained)

Poetry produces music, because things cannot be said [...] when two words that do not know each other, the poet makes them meet with astonishment and invites them to sing with us…

By Gui Minhai, translated by Anne Henochowicz

from The Washington Post

Under the harsh light day and night

I quickly turned into a Père David’s deer

it took only seven hundred days or so

for my graying hair to evolve into antlers

These strange creatures don’t live here

they say my name is “Neither Fish Nor Fowl”

When I was caught I started to evolve

When I started to evolve, I was tamed

As soon as my clothes were peeled away

I became a tamed David’s deer

I sobbed in front of the cameras

admitting I was a deer that had strayed away

In the secret garden, my swift devolution

turned speech into furry groans

turned a hat into a black hood

turned nationality and citizenship into diplomatic dispute

In every Chinese encyclopedia, it is written

that Père David’s deer is a rare beast unique to China

thus one such deer, at ease in the Swedish forest

began a new life in an Asian swamp

I am a devolved David’s deer

unable to choke down poems or prose

but while I am shamed in the swamp

I still yearn to run through the Swedish woods.

first written in prison

rewritten Dec. 10, 2017

To Take Action for Gui Minhai:

Please send appeals to the authorities of China, urging them to:

Release Gui Minhai immediately and unconditionally;

Ensure that, pending Gui Minhai’s release, he is held in conditions that meet international human rights standards for the treatment of prisoners, including by providing him access to adequate health care and regular communication with his family and lawyers.

Send appeals to:

Ambassador CUI Aimin

Role: Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to the Kingdom of Sweden

Email: political@chinaembassy.se

Ambassador CHEN Xu

Role: Ambassador of the Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations Office at Geneva and Other International Organizations in Switzerland

Email: chinamission_gva@mfa.gov.cn

Send copies to the Embassy of China in your own country. Embassy addresses may be found here: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/2490_665344/

Click Here to see how to take action for Maksim Znak, Galal El Behairy, the EritreanWriters, and Freddy Antonio Quezada

Join in demanding justice and freedom for these writers. #FreeTheWriters #MaksimZnak #GuiMinhai #GalalElBehairy #EritreanWriters # FreddyAntonioQuezada

An attack on a writer, the shutting down of a publishing house, the torching of a newspaper reduce the space in the world where ideas can flow. Freedom of expression is vital to writers and to readers but is challenged daily around the world. Listed here are organizations whose work on human rights and in particular issues of freedom of expression I’ve been engaged with directly and indirectly over the years. Some of the organizations have broader agendas, but all have contributed to keeping space open for the individual voice.

PEN International (with its 147 centers in over 100 countries)

PEN American Center

English PEN

PEN/Faulkner Foundation

Human Rights Watch

Amnesty International

Amnesty International USA

International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Article 19

Index on Censorship

Poets and Writers

Authors Guild

International Center for Journalists

I was introduced to Susan Muaddi Darraj’s new novel Behind You Is The Sea, a collection of inner-related stories, at a public event where I bought the book and was quickly drawn into the world of the multi-generational Palestinian immigrant families living in Baltimore. As I read Darraj’s family dramas, I found myself remembering another novel, also structured as interlocking stories about families in love and in conflict, these set in a 1950s fictional Kibbutz Yekhat in Israel. The connection with Amos Oz’s Between Friends was not just the narrative structures, but the humanity of the characters and the relations of generations, the pull of the past and its memories and traditions and the lure of the future for the younger family members—the loyalties and the betrayals.

Neither book dwells on politics or polemics except for the emotional and spiritual angst that affects characters. Neither book requires one to be a member of the community to understand the struggles of values and mores in conflict, with aspirations thwarted or realized by separation.

In Behind You Is The Sea (HarperVia), the reader is brought into the homes of three families—the Ballads, the Salamehs, and the Ammars where we meet the original generation transplanted to America, their children and eventually their grandchildren. The paths of family members diverge but all share in what is essentially an American experience in the melting pot, or is it the mosaic, of a multi-cultural society whose foundations are based on this concept of individuals from many cultures flowing together into one citizenry. Some adjust to their neighbors and others stay isolated; most everyone carries a sense of otherness until one realizes that feeling is part of the human condition in spite of wealth, status or origin.

One of the heroes in the novel, if there is a hero, is Marcus Salameh, a police officer who’s never been to Palestine and who struggles to defend his sister and keep some kind of coherence in his family which has lost his mother and whose father stays alienated in his new land.

Through weddings, birthday parties, funerals—the conventions of family life—the reader experiences the community, the shifting perspectives and the quotidian experiences found in most communities.

The epigraph for Behind You Is the Sea sets out the theme and the momentum of the novel: “You have to be loyal to your exile as much as you are loyal to your homeland.” —Ibrahim Nasrallah

“My mom would have said, in her soft way, ‘Well, Marcus, you are noos-noos, half-Arab, because of us, half-American, because you born here. It doesn’t have to be a problem for you—make it something good.’ And she’d take a puff of her menthol cigarette, lay it back down neatly, and continue stirring the pot. ‘Your brain, your heart—they are two times bigger than everyone else’s,’ she said, marketing it to me like it was a special two-for-one bonus. To my mom, America’s glory was Macy’s One-Day Sale. The 50-percent-off clearance bin at the Dollar Tree. Oh, say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light. The city dump, where you can go to pick up fertilizer and mulch for free. Doctors’ waiting rooms stocked with a coffee bar and jars of mints. That our flag was still there! Mama loved the USA. Even if you got sick and couldn’t pay your bills, the hospital would not throw you out on the street—you sign a paper and, boom, free medical care. Free chemotherapy. Free radiation. And when your hair falls out, the grocery store cashiers who miss seeing you and your coupon wizardry put collection cans on their registers and raise enough money so you can buy a wig.

“So yes, when Baba got worked up about his life, about never going home again, that’s when Mama stepped in, ironed out the wrinkles, and we continued forward as a family. When Walid Ammar says she held us together, it’s obvious, but it’s also goddamned intense and so, so true. Because right now, we are coming apart like a cheap shirt in the wash.”

I don’t recall when I first read Amos Oz’s Between Friends, published in English in 2013 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in the US, but its characters and their dilemmas abided in imagination, committed as they were to an idealistic vision of communal life where members were to be considered equal and working on behalf of each other, where children were considered children of the whole community, and individual parents let go to accept this shared responsibility. But the characters and their ideals confronted human nature inside the kibbutz and the world outside.

Some stayed faithful to their commitment and in doing so sometimes alienated the personal commitment to their individual family members. Members struggled together, helped each other, some tried to learn Esperanto, a language promoted as a “universal language.” Some members had recently survived the Holocaust and gathered in solidarity to be part of a shared vision and responsibility to each other. Their failings in fully realizing this collective dream as it confronted individual aspirations, especially of the younger members and of the world outside, were particular to time and place and also echoed universal themes.

“For a moment, he imagined that he had already left the kibbutz and gone off to a new life, a life without committees, general meetings, public opinion, or the-fate-of-the-Jews. A moment later he thought of Nina Sirota and asked himself if she, like almost everyone else on the kibbutz, would have voted against him tonight. Then he answered his own question: neither Nina nor anyone else on the kibbutz had any reason to support his request, and if it had come from any of the other young people, he himself might have thought, What makes him so special? and would vote with the nays. It was clear to him now that the real issue wasn’t Arthur’s invitation but whether he had enough courage to leave the kibbutz, his mother, and his brother and go out into the world with only the shirt on his back. To that question he found no answer. Thorns and dry leaves stuck to his clothes and he stood up and brushed off his trousers and shirt. Then he began to walk, though what he wanted more than anything was to remain sitting there among the ruins of Deir Ajloun, on the edge of the blocked well, to sit there utterly still, his mind empty of thoughts, and to wait…."

“And once, when two brisk nurses came in to change his pajamas, he grinned suddenly and told them that death itself was an anarchist. ‘Death is not awed by status, possessions, power, or titles; we are all equal in its eyes….’

“Then Yoav Carni, representing the secretariat, gave a short eulogy. He pointed out that Martin had been alone all his life, a survivor who had hidden in Holland during the Holocaust. ‘He saw with his own eyes how low human beings could sink, but still he came to us imbued with belief in people and in a future burning with the bright flame of justice. We were often surprised,’ Yoav said, ‘at his honesty and devotion to his ideals.’”

Sharing here a scene and passage of text from The Far Side of the Desert’s opening, set in Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

(Over the years I’ve accumulated a running list of words I haven’t known from two main sources: WordDaily and WordGenius)

Pangloss

/paenglos/

Part of speech: noun

1. A person who is optimistic regardless of circumstances.

Examples:

"As the storm soaked through our tent, my Pangloss of a husband suggested it was a chance to test our waterproof sleeping bags."

"When our flight was delayed, the Pangloss in front of me cheered for the opportunity to get a meal at the airport."

"My sister can find the silver lining in almost any situation, but she's also a realist, not a Pangloss."

Bedizen

/bəˈdīzən/

Part of speech: verb and adjective

1. Dress up or decorate gaudily.

Examples:

“I don’t want to fade into the background; I want to be bedizened with rhinestone and sparkles.”

“After high school prom and maybe weddings, there aren’t many opportunities to bedizen yourself.”

“Will you bedizen yourself for the gala with me?”

Haptic

/haep tik/

Part of speech: adjective and noun

1. Relating to the sense of touch, in particular relating to the perception and manipulation of objects using the sense of touch and proprioception.

2. The use of technology that stimulates the senses of touch and motion, especially to reproduce in remote operation or computer simulation the sensations that would be felt by a user interacting directly with physical objects.

3. The perception of objects by touch and proprioception, especially as involved in nonverbal communication.

Examples:

“The latest model of that tablet replaced the click buttons with a haptic system."

”Touch-screen devices have trained people to be more responsive to haptic sensations.”

“Dogs can be trained using haptics just as easily as using voice commands.”

I’ve spoken at bookstores, university classes, book luncheons and in-person and zoom book clubs and look forward to more ahead. I enjoy giving readings and addressing audiences in many venues and moderating discussions on a wide range of topics and most of all meeting readers.

Click here for a list of future and past public events.

Or fill out the speaking request form to schedule an event.

I like engaging with readers so if you are in a Reading Group or Book Club and read one of my books, I’m glad to be in touch by email, zoom, or when possible in person. I can also suggest discussion topics.

Fill out the reading group form here to schedule a meeting.