Finding Kindness and Heroes

Dear Friends,

Welcome to August’s Substack.

I hope you’ll enjoy this month’s blog Finding Kindness and Heroes. The audio version is available by clicking the link in the blog or clicking the link here for all podcasts. https://joanneleedomackerman.substack.com/podcast

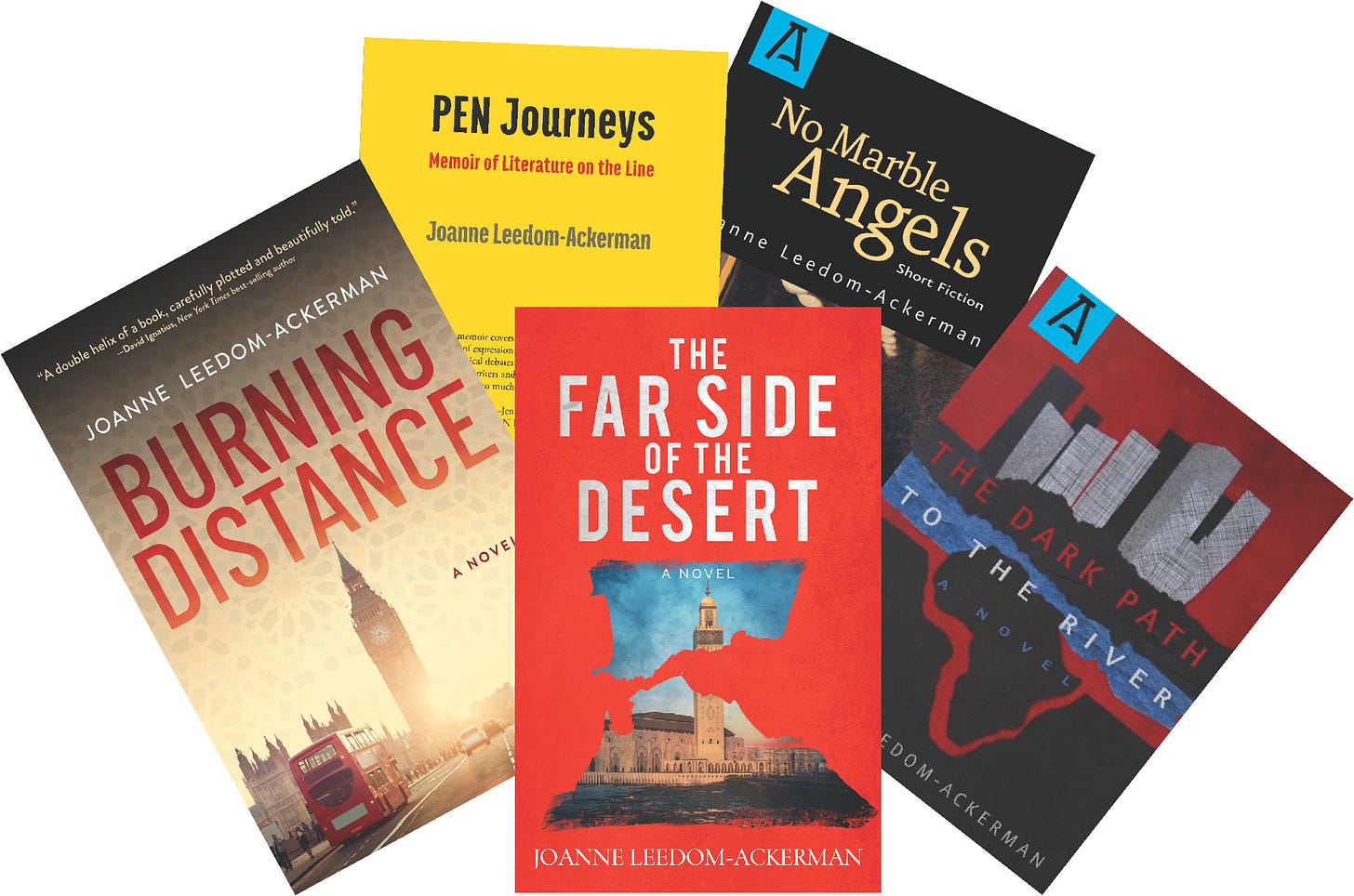

Book News shares new awards, interviews, podcasts and information on my novels and notes the recent paperback publication of The Far Side of the Desert.

The Writers at Risk section focuses on award-winning Algerian/French novelist Boualem Sansal who faces five years in Algerian prison.

The Books to Check Out section looks back a century and profiles A.A. Milne’s The Red House Mystery and to the sixties to Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls.

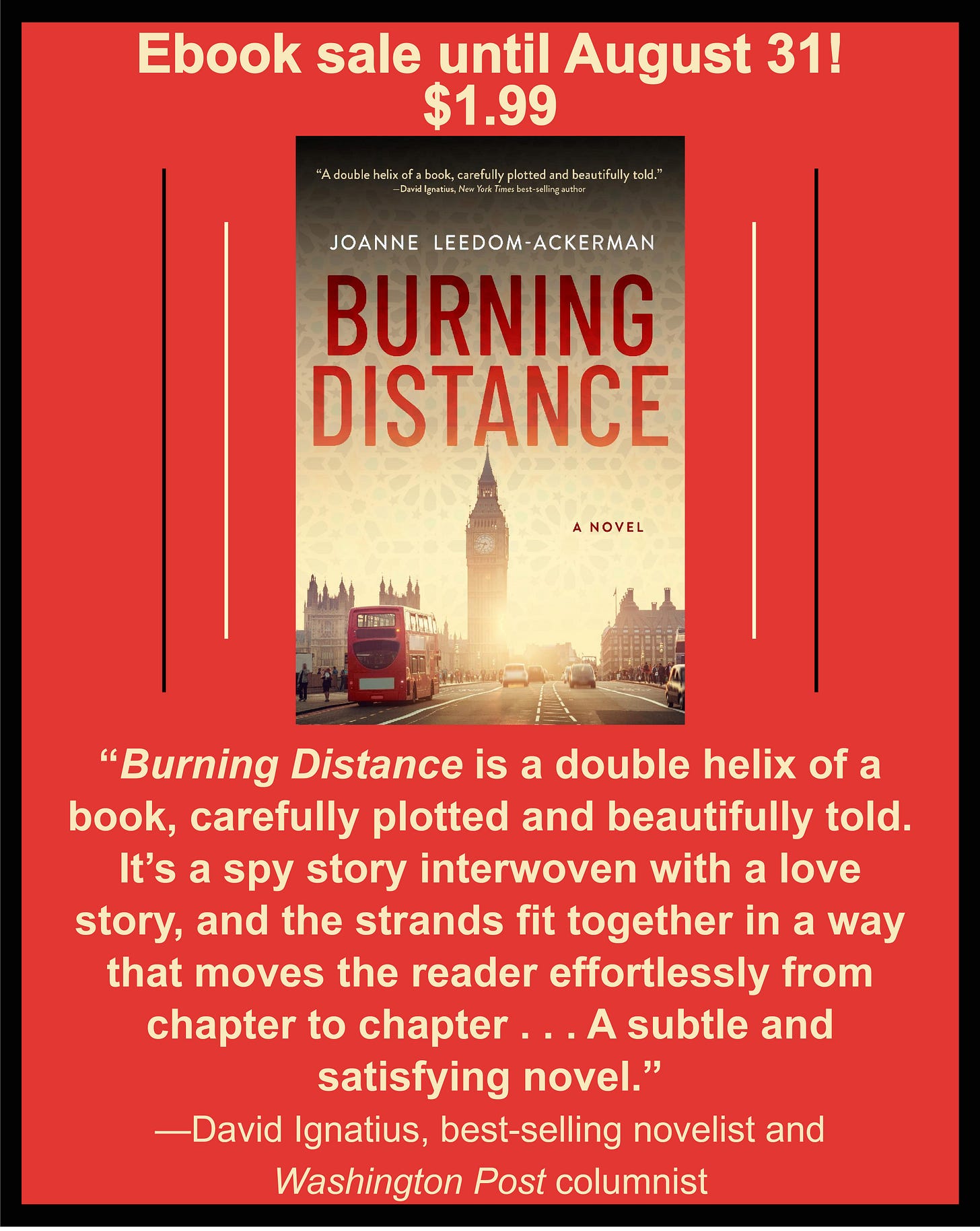

In the Scene section you’ll find a photo, along with text from Burning Distance, and in Words of the Month a couple of words you may not use but might like to know.

Thank you to everyone who has come to bookstores, libraries, book clubs and online for my latest novels Burning Distance and The Far Side of the Desert. Word of mouth is what sells books, connecting them to readers. Thank you for spreading the word!

If you’re interested in having me speak at a venue or with a book club, click here. Thank you too for reading and sharing this free monthly Substack On the Yellow Brick Road. I hope you’ll stay in touch!

Finding Kindness and Heroes

Last month’s Substack essay “In Search of Kindness” follows up here with acts of kindness observed.

I was recently visiting my old neighborhood in London where I used to live, walking down High Street Kensington on a sunny July day. The High Street was bustling with people—residents, tourists, children, darting in and out of the High Street Kensington tube station and in and out of shops and hurrying on to their next destinations. I was on my way to a favorite restaurant when a diminutive woman in a loose blue shirt caught my eye. I was walking behind her. She had short grey hair and was slightly bent over, a person you might not notice, except I noticed that when she passed an elderly man folded into a doorway with a paper cup in front of him, she reached into her purse, took out several coins and went over to him and dropped them into his cup. No one else had noticed him.

Half a block later another elderly man with a full gray beard sat in the corner of a building on the High Street playing tentatively on a guitar. Again, she reached into her purse and made the effort to move across the insistent flow of pedestrians and dropped a few coins into his guitar case. No one else was stopping. This was not the mission of her outing, but she paused and took note of these people then went on her way.

I was certain she would do the same for the next itinerant down the block. I stepped up beside her and said, “You’re a good woman. I saw you helping.” She looked over at me surprised that I’d noticed then she smiled. “It isn’t going to hurt me to give a little,” she said.

“You saw them and showed that you cared,” I observed. She appreciated this insight.

“They are often here,” she said. Our conversation wasn’t long, and she went her way into the shops.

I had no coins, living as we do now by credit cards, not cash, but I went into the next shop and got cash and filled my own pocket with coins. I think we both understood that these coins would not solve the problems of unemployment or homelessness, or perhaps even be able to change much the circumstances of those who’d slipped into the corners of the street, but the gesture at least showed that they were seen. Those few who were also playing musical instruments—guitars and violins which perhaps were once tools of their trade—also shared music with the street as pedestrians rushed by.

One cannot fund all who find refuge on street corners these days. And it is important in giving not to be funding habits of drugs, but many have simply fallen out of the system of employment or social services. The larger societal answers are left to those who work in social service organizations or government agencies. I recognize that giving a few coins or bills is neither the answer nor everyone’s responsibility, but I also noticed how few in the hundreds rushing by paused or noticed. Have we gotten numb to hardship, perhaps even annoyed by it, even receptive to those who blame the victims?

While in London, I went to the theatre and saw a play “Till the Stars Come Down” about a Midlands English family wedding where the prejudice is against the Polish groom in a town where coal mines have closed. At one point the Polish groom says to his unemployed and prejudiced brother-in-law to whom he’s offered a job: “You need to decide if you’re a victim or superior because you can’t be both.” The play’s theme threads through the story and characters, demonstrating the corrosive nature of prejudice which can hollow out the heart, feelings and human spirit, whether that prejudice is racial, national, religious, or...

The same day I observed the elderly woman reaching into her purse on the High Street, a news story was reported out of France about a caretaker at a public middle school in Paris who arrived home tired after a week of work, but instead of resting heard a fire alarm nearby and went to check it out. There he spotted a woman and her children trapped by the fire calling for help. He climbed onto a ledge of the sixth floor where he took the children from the burning building one by one and got everyone, including two infants and the mother—six people—to safety.

He scaled the building to help. “I went on instinct,” he said. “It’s the heart telling you, ‘No, you have to go.’”

It is the heart telling you.

I’m honored that The Far Side of the Desert (Oceanview Publishing) was recently named as a finalist in the Suspense category for the 2025 National Indie Excellence Awards. The novel was also awarded the 2025 Bronze medal in the Suspense/Thriller category by the Independent Publishers Association (IPPY) Book Awards.

Published in 2024, The Far Side of the Desert was released in paperback April, 2025. I hope you’ll order, read and enjoy. If you’ve already read the hardcover, I hope you’ll buy the paperback and give to friends!

“The Far Side of the Desert by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman is a razor-sharp tale of sisters, daughters, spies, and lovers; some relatable, some who appear to be beyond redemption, and some whose acts of good or evil are much harder to tease apart. Deftly managing the tightrope between the tightly-paced geopolitical and the nuanced psychological, Leedom-Ackerman delivers a thriller that transcends genre and has stayed with me long after I read it in one breathless sitting. The Far Side of the Desert is one of my top reads this year!”

—Deborah Goodrich Royce, nationally bestselling and award-winning author of Reef Road, Ruby Falls, and upcoming Best Boy

Burning Distance is currently available for summer reading in ebook format for only $1.99. You can purchase from any ebook seller online through August 31.

Burning Distance (Oceanview Publishing, 2023 and paperback in 2024) was honored by the 2024 American Book Fest International Book Awards as a Finalist in the Best Mystery/Suspense and Thriller/Adventure categories.

“Burning Distance opens with a mystery, glides into a love story, and unfolds into a political thriller. Set against the backdrop of 1980s and 90s global politics, readers will be up way past their bedtimes eagerly turning pages to discover what happens to Lizzy and Adil. A story of war, family, history, politics, and passion. Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’s evocation of the era is pitch-perfect. A great read!”

—Susan Isaacs, New York Times best-selling author of It Takes One To Know One

Thanks to Monica Hadley and Writers Voices for the recent interview about The Far Side of the Desert. You can listen here.

Selected recordings of past events and interviews:

Interview with Monica Hadley, Writers Voices

Strategies for Living Podcast: Finding Resilience Through Story

Interview with Janeane Bernstein on NPR’s KUCI, Get the Funk Out!

Book Launch for Akram Aylisli's People and Trees with Plamen Press

Why Baldwin Matters Series, The Alan Cheuse International Writers Center

Malaprop’s Bookstore and Café in Asheville, NC

Kinokuniya Bookstore in New York City with Salil Tripathi

Baum on Books on WSHU Public Radio

Interview with Anna Roins of Authorlink

Interview with Deborah Kalb

For more podcasts, videos and interviews, click here

Boualem Sansal (Algeria)

بوعلام صنصال

(Sources include PEN International, American PEN, FRANCE 24, Le Monde, The European Conservative)

Algerian-French writer Boualem Sansal is caught in a political vortex. An award-winning novelist, he was recently sentenced to five years in prison in Algeria on charges of “undermining national unity,” “insulting state institutions,” and “possessing media and publications threatening the country's security and stability.”

A former senior official in Algeria’s Ministry of Industry with an engineering degree and a PhD in economics, Sansal began writing almost thirty years ago at age 50 and is the author of novels that have received major prizes and international acclaim, including the Prix du Roman Arabe and the Grand Prix du Roman from the French Academy.

According to Sansal, the assassination of President Mohamed Boudiaf in 1992 and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Algeria inspired him to write about his country. His novel Le village de l'Allemand ou le journal des frères Schiller, tells the story of two Algerian brothers who discover their father had been a Nazi officer who fled to Algeria after the war. The book examines the line between Islamic fundamentalism and Nazism. Translated into English, Le Village de l'allemand was published in the US as The German Mujahid and in the UK as An Unfinished Business.

Even as his criticism of Islamic extremism and his books stirred controversy, Sansal continued to live in Algeria with his wife and two daughters. He’s been called a writer “exiled in his own country” which he claimed was becoming a “bastion of Islamic extremism, losing its intellectual and moral underpinnings.” He was also accused of giving an interview to conservative Frontières magazine a month before his arrest, in which he questioned Algeria’s claim to territories that historically belonged to Morocco during the French colonial era.

In 2024 Sansal was granted French citizenship. On 16 November 2024, Algerian authorities arrested him on his arrival at Algiers airport. For over a week his whereabouts was unknown, and he was denied access to his family and legal counsel and interrogated in the absence of his lawyer, who was not allowed into Algeria.

On January 23, 2025, the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for his immediate release. Algerian lawmakers signed a statement rebuking the European Parliament's resolution, which they said contained "misleading allegations with the sole aim of launching a blatant attack against Algeria." The Arab Parliament also condemned the European Parliament's resolution, calling it "irresponsible" and a "blatant and unacceptable interference" in Algeria's domestic affairs, and calling on the European Parliament to "respect the decisions of the Algerian judicial system."

At his trial Sansal represented himself. During the appeal trial in June, the Algerian prosecutor attempted to double his sentence, but the appeals court upheld the five-year prison term and fined Sansal 500,000 Algerian dinars ($3,730).

Sansal has gone on a hunger strike and is said to be in poor health. His daughters, who now live in Prague with their Czech mother, requested a presidential pardon from Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune. Assisted by Czech Ambassador Jan Czerný, the plea was submitted through the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but no pardon has been received.

“We are outraged by the court’s decision to uphold Boualem Sansal's sentence, signaling a zero-tolerance policy towards government critics. Sansal’s persecution highlights the dreadful status of freedom of expression in today’s world, where writers are being arrested, face unfair trials, and imprisoned for their views. We call on Algerian authorities to quash Sansal’s conviction and release him immediately,” said Burhan Sonmez, President of PEN International.

To Take Action for Boualem Sansal:

Urge the Algerian government to:

Immediately and unconditionally release Boualem Sansal

Guarantee Boualem Sansal’s safety and access to adequate and independent care.

Allow him unhindered access to her family members and lawyer of his choosing.

Send Appeals to:

Please send your letters via the the Embassy of Algeria in your country. Addresses could be found here.

An attack on a writer, the shutting down of a publishing house, the torching of a newspaper reduce the space in the world where ideas can flow. Freedom of expression is vital to writers and to readers but is challenged daily around the world. Listed here are organizations whose work on human rights and in particular issues of freedom of expression I’ve been engaged with directly and indirectly over the years. Some of the organizations have broader agendas, but all have contributed to keeping space open for the individual voice.

PEN International (with its 147 centers in over 100 countries)

PEN American Center

English PEN

PEN/Faulkner Foundation

Human Rights Watch

Amnesty International

Amnesty International USA

International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Article 19

Index on Censorship

Poets and Writers

Authors Guild

International Center for Journalists

I spent part of July in London where I’ve lived off and on and visit whenever I can. For an English literature major, the journey begins in London. On this visit wandering in Waterstones bookstore, I stopped at a table of “Mystery Books” and there spotted a book by A.A. Milne. I didn’t know the celebrated author of Winnie the Pooh had also written a detective novel so I bought it.

On the flight over to London, I considered a list of “The 20 best novels of all times” in the London Telegraph, eleven and a half of which I’d read. I’ve yet to finish Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, but I’ve read Joyce’s Ulysses twice (in graduate school.) I questioned several on the list and decided to read one of these—Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls (1960), set in Ireland. I wouldn’t have put it on such an exclusive list but am glad to have read it.

Both of the novels in this month’s column are from times past, both rooted in the United Kingdom, and if not standing the longer test of time, they take the reader back through the years both in story and in style.

It turns out that Alan Alexander Milne was known at the time as a humorist, writing for Punch magazine and eventually becoming its editor. In the introduction of The Red House Mystery he writes: “When I told my agent a few years ago that I was going to write a detective story, he recovered as quickly as could be expected, but made it clear to me (as a succession of editors and publishers made it clear, later, to him) that what the country wanted from ‘a well-known’ Punch humorist was a ‘humourous story.’ However, I was resolved upon a life of crime; and the result was such that when two years afterwards, I announced that I was writing a book of nursery rhymes, my agent and my publisher were equally convinced that what the English-speaking nations most desired was a new detective story.”

The Red House Mystery was published in 1922 before Agatha Christie’s first book. The great detective stories and writers were only beginning to emerge between the two World Wars. Milne knew many of the writers of his day, in part from playing amateur cricket together, including J.M. Barrie (Peter Pan), P.G. Wodehouse and Arthur Conan Doyle to whom Milne pays tribute in The Red House Mystery, referencing his version of Sherlock Holmes and Watson. Though his novel sold widely and well, The Red House Mystery is Milne’s only contribution to the detective/mystery genre.

Between 1924-1928 Milne wrote two books of children’s verse When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six and the two small story books Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner, four books totaling barely the size of his one detective novel but which made him rich, famous and an author for the ages. These four slim books are the ones remembered rather than his 18 plays, four screenplays, three novels and three collections of journalism and endless columns from Punch, all of which slipped away into the period from which he wrote.

In his autobiography It’s Too Late Now, Milne confesses his thinking towards his own work: “It has been my good fortune as a writer that what I have wanted to write has for the most part been saleable. It has been my misfortune as a businessman that, when it has proved extremely saleable, then I have not wanted to write any more.”

The Red House Mystery, classic in form and characters, doesn’t outshine the Agatha Christie and Conan Doyle novels which came to define the genre in the early 20th century, but true to form it exposes conventional thinking and the misapprehensions of the official detectives. And it ends with a major plot twist. The Holmes-like amateur detective Anthony Gillingham figures out the guilty party who killed the alleged ne’er-do-well brother visiting from Australia.

The novel’s characters include stock English visitors to a country-house weekend, including a retired major, a widow and her attractive single daughter, a young dilettante estate owner and his “protégé” secretary and beneficiary of his largess. A murder occurs at the beginning of the novel. The suspected murderer has disappeared and off to races with the detective skills of the virtual stranger Gillingham, friend of one of the guests, called upon to compete with the local, more conventional constabulary.

The Red House Mystery was poplar in its time, but those more skilled and committed to the genre took on the mantle and outpaced A.A. Milne in this form.

But few have overtaken A.A. Milne’s Christopher Robin and Edward Bear, better known as Winnie-the-Pooh.

From The Red House Mystery:

In the drowsy heat of the summer afternoon the Red House was taking its siesta. There was a lazy murmur of bees in the flower-borders, a gentle cooing of pigeons in the tops of the elms. From distant lawns came the whir of a mowing-machine, that most restful of all country sounds; making ease the sweeter in that it is taken while others are working.

It was the hour when even those whose business it is to attend to the wants of others have a moment or two for themselves….

“You could have knocked me down with a feather when he spoke about him at breakfast this morning. I didn't hear what went before, naturally, but they was all talking about the brother when I went in—now what was it I went in for—hot milk, was it, or toast?—well, they was all talking, and Mr. Mark turns to me, and says—you know his way—'Stevens,' he says, 'my brother is coming to see me this afternoon; I'm expecting him about three,' he says. 'Show him into the office,' he says, just like that. 'Yes, sir,' I says quite quietly, but I was never so surprised in my life, not knowing he had a brother. 'My brother from Australia,' he says—there, I'd forgotten that. From Australia."

"Well, he may have been in Australia," said Mrs. Stevens, judicially; "I can't say for that, not knowing the country; but what I do say is he's never been here."

The rationale for including Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls in The Telegraph’s “20 best novels of all times" is quoted below. I wouldn’t have included this novel on the same list as War and Peace, Ulysses, Moby Dick, Middlemarch, or Invisible Man, but its charm and dialogue and the circumstances of two Irish teenagers opens a window to the time and place and the insatiable longing to know more and find a larger world.

The Telegraph’s Claire Allfree writes: “In provincial 1950s Ireland, two girls walk out of their Catholic boarding school, head to Dublin, and start a revolution – or, rather, O’Brien’s account of their lives did. The seismic impact of O’Brien’s debut novel (which became a trilogy) has reverberated throughout Ireland and its literature ever since. Through the tender and messy lives of two close friends, Cait and Baba, both 14 when the first novel begins, O’Brien revealed the longings of young women in what was then still a repressively conservative Ireland. Her writing is exquisite, giving us the perspective of its two protagonists, both simultaneously naïve and knowing. Generations of Irish writers from Anne Enright to Sally Rooney and Eimear McBride have acknowledged their debt.”

From The Country Girls:

It was a wet afternoon in October, as I copied out the September accounts from the big gray ledger. I worked in a grocery shop in the north of Dublin and had been there for two years.

My employer and his wife were country people like myself. They were kind, but they liked me to work hard and promised me a raise in the new year. Little did I know that I would be gone by then, to a different life.

Because of the rain, not many customers came in and out, so I wrote the bills quickly and then got on with my reading. I had a book hidden in the ledger, so that I could read without fear of being caught.

It was a beautiful book, but sad. It was called Tender Is the Night. I skipped half the words in my anxiety to read it quickly, because I wanted to know whether the man would leave the woman or not. All the nicest men were in books—the strange, complex, romantic men; the ones I admired most.

I knew no one like that except Mr. Gentleman, and I had not seen him for two years. He was only a shadow now, and I remembered him the way one remembers a nice dress that one has grown out of.

At half past four I put on the lights. The shop looked shabbier in artificial light, too; the shelves were dusty and the ceiling hadn’t been painted since I went there. It was full of cracks. I looked in the mirror to see how my hair was. We were going somewhere that night, my friend Baba and me. My face in the mirror looked round and smooth. I sucked my cheeks in, to make them thinner. I longed to be thin, like Baba.

“You look like you were going to have a child,” Baba said to me the night before, when I was in my nightgown.

“You’re raving,” I said to her. Even the thought of such a thing worried me. Baba was always teasing me, although she knew I’d never done more than kiss Mr. Gentleman.

“It happens to country mopes like you, soon as you dance with a fellow,” Baba said, as she held an imaginary man in her arms and waltzed between the two iron beds. Then she burst into one of her mad laughs and poured gin into the transparent plastic tooth mugs on the bedside table.

Sharing here image and passage of text from Burning Distance:

Dad once predicted: “Jane will be the first woman president. Sophie will be secretary of state, and Lizzy will be a peacemaker.”

As I prepared to enter George Washington University that summer of 1989, I found myself thinking about Dad’s words. Jane was a full-time reporter for Newsday covering state and national politics and hoping to shift to The New York Times—not a career path to the presidency, though she watched over government agencies and politicians like a hawk. Sophie was a senior at Brown University, planning to attend graduate school in international relations, a path that could land her at the State Department. I had no idea what I would be good at. I wondered why Dad had given Jane and Sophie job titles and only given me a vocation. What was a peacemaker anyway? I looked at my future like a vast uncharted ocean I had to make my way across.

I spent the summer working for Mom at the magazine, reading books from a college list and sunbathing in Kensington Gardens. The summer was one of the hottest and driest on record in London. It was a summer of change and movement in Europe, particularly for the people in Eastern Europe who were agitating against their Communist regimes and pressing at their borders.

(Over the years I’ve accumulated a running list of words I haven’t known from two main sources: WordDaily and WordGenius)

Meliorism

[meel-yuh-riz-uhm]

Part of speech: noun

1. the doctrine that the world tends to become better or may be made better by human effort.

Examples:

“He explained, ‘In the spirit of American meliorism, the criticism is to make things better, not necessarily because I didn’t like it.’”

“What if the real way forward weren’t a great leap but grinding, tedious, unglamorously incremental change—what George Eliot called ‘meliorism’?”

“For some realists, ‘global meliorism’— the belief that U.S. foreign policy can and should try to make a better world—is a dirty word.”

Cormorant

[kawr-mer-uhnt]

Part of speech: noun

1. any of several voracious, totipalmate seabirds of the family Phalacrocoracidae, as Phalacrocorax carbo, of America, Europe, and Asia, having a long neck and a distensible pouch under the bill for holding captured fish, used in China for catching fish.

2. a greedy person.

Examples:

“And populations of once-numerous birds such as American white pelicans, double-breasted cormorants and eared grebes have declined.”

“And populations of once-numerous birds such as American white pelicans, double-breasted cormorants and eared grebes have declined.”

I’ve spoken at bookstores, university classes, book luncheons and in-person and zoom book clubs and look forward to more ahead. I enjoy giving readings and addressing audiences in many venues and moderating discussions on a wide range of topics and most of all meeting readers.

Click here for a list of future and past public events.

Or fill out the speaking request form to schedule an event.

I like engaging with readers so if you are in a Reading Group or Book Club and read one of my books, I’m glad to be in touch by email, zoom, or when possible in person. I can also suggest discussion topics.

Fill out the reading group form here to schedule a meeting.

Terrific piece Joanne. I often tell the story of the priest at the church I attend who said in his homily “When you see a beggar you may not want to give him anything because you think he will spend the money on wine or beer. But have you considered that this may be the unfortunate person’s only little pleasure in life. Do you want to deny him. No, give him the money.”

The stories about those helping neighbors touch my heat...I love the man who scaled the burning building to rescue a family. “I went on instinct,” he said. “It’s the heart telling you, ‘No, you have to go.’” As you write, "It is the heart telling you."

Thanks for sharing.