On the Edge of the UN

Dear Friends,

Welcome to October’s Substack, my third on this new platform.

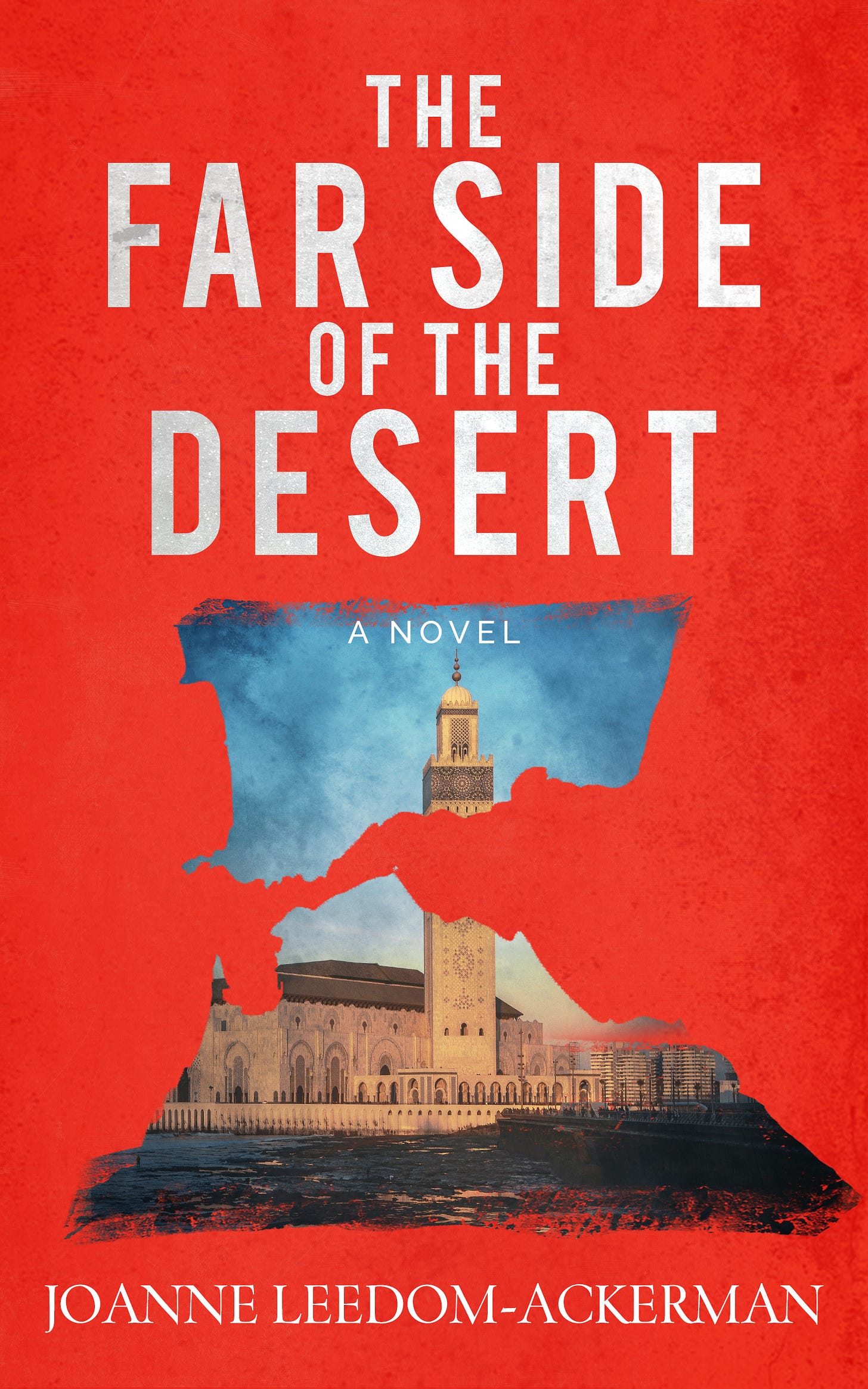

I continue to prepare for the launch of my next novel The Far Side of the Desert to be published March 5, 2024 and the paperback of Burning Distance due out in February with the first chapter of the new book included. Thank you to readers who’ve shared their enthusiasm for Burning Distance and left reviews on Amazon and elsewhere and told friends. You’ll see in this Substack a special offer from my publisher Oceanview for Burning Distance in October.

This month’s blog post On the Edge of the UN muses on the world order, the streets of New York during the UN General Assembly, and also pays tribute to a champion of the free press—Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

In the Writer at Risk section, I’ve focused on the story of Ilhan Sami Çomak, Turkey’s longest serving writer in prison and on his moving poetry.

There is pairing of two charming books in the Books to Check Out and in Words of the Month are words you may not know, never use, but may find interesting.

I hope you’ll enjoy this installment of “On the Yellow Brick Road” SubStack, share it and encourage friends to sign up. It’s free.

Here’s to a fall full of books and ideas,

Joanne

My latest novel, The Far Side of the Desert, will be published March 5, 2024 by Oceanview Publishers and is available now for pre-order!

I’m happy to see the $1.99 Kindle Special for my novel Burning Distance continue through the month of October! I hope you’ll enjoy Burning Distance, write a review and if you see a similarity with Burning Distance’s ending and a current event, let me know in the comments section or on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter/X or LinkedIn, and I’ll send you a signed copy!

Thank you to the American Writers Museum for featuring Burning Distance as one of the September Staff Picks. Congratulations to the other authors as well!

On the Edge of the UN

The week of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) meeting is full of targeted and chaotic energy from around the world. I was there by chance last year with all the traffic snarls, blocked streets and crush of crowds, especially on the day the U.S. President was in town. I vowed to avoid that week forevermore.

But this year with a meeting I could only get on Monday and another on Friday and various events and meetings in between during mid-September, I called to book a hotel, only to find hotels were sold out and the price of the few available rooms had skyrocketed. Alas, I realized it was the week of the UNGA.

I finally managed to find a hotel not costing the price of a car down payment. With more experience, I scheduled meetings I could walk to, and, with the exception of the first day when torrents of rain doused the city, the weather cooperated with sunny fall days. New York bristled with the added energy of the United Nations General Assembly as delegates from around the world walked the streets in all the finery and dress from African, Asian, and Latin American countries.

The larger question is what was accomplished at the UN General Assembly. That remains to be seen at this writing, but there are a few hopeful signs. At the least there is something heartening about seeing representatives from the nations of the world come together in anticipation of getting along long enough to solve global problems affecting us all like climate, migration, and armed conflict.

For those of us born after World War Two—and that now includes most of the world’s population— there is a compelling desire to avoid such a conflagration again. Those who witnessed with optimism the fall of the Berlin Wall and a turn towards democratic government in Eastern Europe and around the world in the 1990s are now alarmed by the return of authoritarianism. Signs of stress on the international governing systems are mounting.

There continues to be a need beyond the United Nations for international forums where problems can be addressed and solutions crafted. In August I had the opportunity to visit one institution which keeps watch over a crucial pilar of free societies—the free press with its free flow of information. In late summer I visited Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) whose mission is to promote democratic values and report accurate, uncensored news in countries where the press is threatened and disinformation abounds.

Headquartered in Prague on a secure and sprawling campus, RFE/RL employs 700 journalists around the world to research, write and broadcast stories that uncover corruption and advocate for free societies and their institutions like independent judiciaries and free press. With large newsrooms and correspondents who report the news in 27 languages in 23 countries where a free press is banned or works under threat, RFE/RL is on the front lines.

As the newsrooms of traditional press shrink and the numbers of foreign correspondents dwindle, it was heartening to walk through the halls and newsrooms at RFE/RL and sit around a table with experienced journalists from Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America who have resources available to investigate and report critical stories. Logging a weekly audience of 40 million and 869 million yearly visits to its website and 15 billion annual video views, RFE/RL is one of the most comprehensive news operations in the world with 21 local bureaus and an additional 1300 freelancers and stringers plus two bureaus in the U.S.

Approximately 1500 hours of radio programming are also broadcast every week where listeners can tune in on shortwaves. RFE/RL has a network of partner organizations that rebroadcast across 11 time zones. However, in the current climate, rebroadcasting is prohibited on local outlets in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Iran, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, and journalists are under increasing threat and censorship. RFE/RL’s website has been blocked in Crimea, its broadcasts jammed; the website is blocked in Iran where the bureau was closed and banned from FM and the Internet in Azerbaijan, and the accreditation stripped from journalists in Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Registered as a private, nonprofit corporation, RFE/RL is funded by a grant from the U.S. Congress through the United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM) as a private grantee. Major policy decisions are made by its independent Board of Directors, the majority of whom are career journalists and human rights specialists. To guarantee journalistic credibility, a “firewall” was part of the enabling legislation and prohibits interference by U.S. government officials, including USAGM’s Chief Executive Officer, with the objective of producing independent reporting of the news. Journalists and editors make the final decisions on what stories to cover and how they are covered, according to Jeffrey Gedmin, the interim CEO of RFE/RL.

Recent RFE/RL stories include lengthy investigations into corrupt practices in Russia where it reaches Russian-speaking audiences and beyond via the Current Time digital and 24/7 television network. Other stories include reports on the cease fire between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan’s military operations in the region; Ukrainian infantry breaking though Russian defenses, including a live briefing of Russia’s invasion; Iranian deputies vote to toughen penalties for women flouting the dress code; Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili’s trial in Tbilisi.

Ilhan Sami Çomak (Turkey)

(Source PEN, including PEN Norway)

In Turkey where writers have been regularly detained and imprisoned, Kurdish poet Ilhan Sami Çomak is one of the longest serving, sentenced to life in prison for membership in the banned Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). As a university student, he was arrested in 1994 on what he insists were false charges of starting a forest fire and association with the PKK. After 19-days of torture, he signed a false confession. He was not originally imprisoned for his writing, but in prison he has written and published eight books of poetry, many written in solitary confinement in the high security Silivri prison. His main company during much of this time is said to be a small pet bird.

In 2007 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Çomak’s prosecution was unlawful, but he was not released. The conviction was again appealed in 2013 and in 2016.

“They didn’t listen to him, to his lawyers and to the witnesses at all,” reported his official visitor, the campaigner Ms. Ipek Özel.

Ilhan Sami Çomak is now regarded as an important Turkish poet. In 2018 Çomak won the Sennur Sezer poetry prize for his book Geldim Sana (I Came to You). He received the Norwegian Writers' Union Freedom of Expression prize in 2022 and the Metin Altıok poetry prize in the same year. Also, in 2022 PEN Norway published, along with Smokestack Books, 50 of his poems in English in a volume entitled Separated from the Sun. His poem What I know of the Sea appeared on the London Underground as part of the “Poems on the Underground” series.

His work and his situation have been compared to that of other renowned imprisoned Turkish poets, including Nazim Hikmet.

This past spring Ilhan Çomak’s application for a supervised release was dismissed even though he had met all the conditions, according to his counsel.

“Ilhan has the right to enjoy probation with the implementation of supervised release rights under Article 105A of Law No. 5275…Ilhan’s prison report card is very, very successful and even more all the staff in the prison, some of whom are the members of the (parole) committee have warm human relations with him…” said Ms. Özel.

“I was shocked…He was calm when he gave me his news. He said that he was used to the injustice. The only thing he wanted me is not to be upset….I do not need to go further and say that this decision is a disappointment.

“I would like to request support once again to bring this justice. If writers and thinkers, lawyers and influential people would like to cooperate to raise Ilhan’s voice to the world again, I am ready to give all kinds of support here and we will really be grateful for that,” writes Ms. Özel.

In Ayça Turkoglu’s review of Separated from the Sun in Modern Poetry in Translation he notes:

“Why write poetry in prison? In his own words, Çomak writes to ‘search [for] … the life that was stolen from me; I am seeking my lost happiness and contentment.’ The poems featured in Separated from the Sun reveal little bitterness. Instead, Çomak brings the outside in with poems rich in the imagery of the natural world; the sky and birds feature heavily in these poems, as do green spaces, running water, and the chance of freedom….In ‘I came to you, life’, translated by Caroline Stockford, he writes:

Open the window. Open it as the horses whinny

in the wideness of the world

…Ever conjuring ‘things that are not here’, Çomak’s poetry nevertheless remains optimistic, with a sense of momentum and energy that builds throughout the collection. In ‘Freedom’ (translated by Caroline Stockford), Çomak is defiant, committed to writing his own story, with an eye to the future:

It’s time to breathe the smell of soil, fill with it, grow with it

Know me by my love, not by my loneliness

[…]

I’m coming in search of you.”

Poem by Ilhan Sami Çomak:

Life, separated from the sun

There’s no direction here

But here is a way out

Always a way out.

—Ilhan Çomak

“The contentment of my childhood years and my imagination was enough to ensure that I lived my whole life in happiness. When that peace was lost, the happiness too was taken with it. The only thing I have left now is the power of my imagination… I have many reasons, of course, for writing poetry. However, I should like to emphasise most strongly that I am in search of the life that was stolen from me; I am seeking my lost happiness and contentment. I was a lovely child. I really miss and love the little child that I was. That is why I write poetry. For him.” —Ilhan Sami Çomak

The anthology with Ilhan’s poems is due out next year. Ilhan’s readers and supporters hope that 2024 might also see his release.

Ilhan Sami Çomak is one of 23,000 prisoners in Turkey’s highest security Silivri Prison.

To Take Action:

Write to him:

Ilhan Sami Çomak,

Silivri High Security Prison,

F9 ALT, SILIVRI, İSTANBUL,TURKEY

Write to Turkey's Ambassador to your country

https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkish-representations.en.mfa

Write to Turkey's Minister of Justice:

Mr Abdulhamit Gül,

Hukuk Birimi

06659 Kızılay

Ankara/Turkey

An attack on a writer, the shutting down of a publishing house, the torching of a newspaper reduce the space in the world where ideas can flow. Freedom of expression is vital to writers and to readers but is challenged daily around the world. Listed here are organizations whose work on human rights and in particular issues of freedom of expression I’ve been engaged with directly and indirectly over the years. Some of the organizations have broader agendas, but all have contributed to keeping space open for the individual voice.

PEN International (with its 147 centers in over 100 countries)

PEN American Center

English PEN

PEN/Faulkner Foundation

Human Rights Watch

Amnesty International

Amnesty International USA

International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Article 19

Index on Censorship

Poets and Writers

Authors Guild

International Center for Journalists

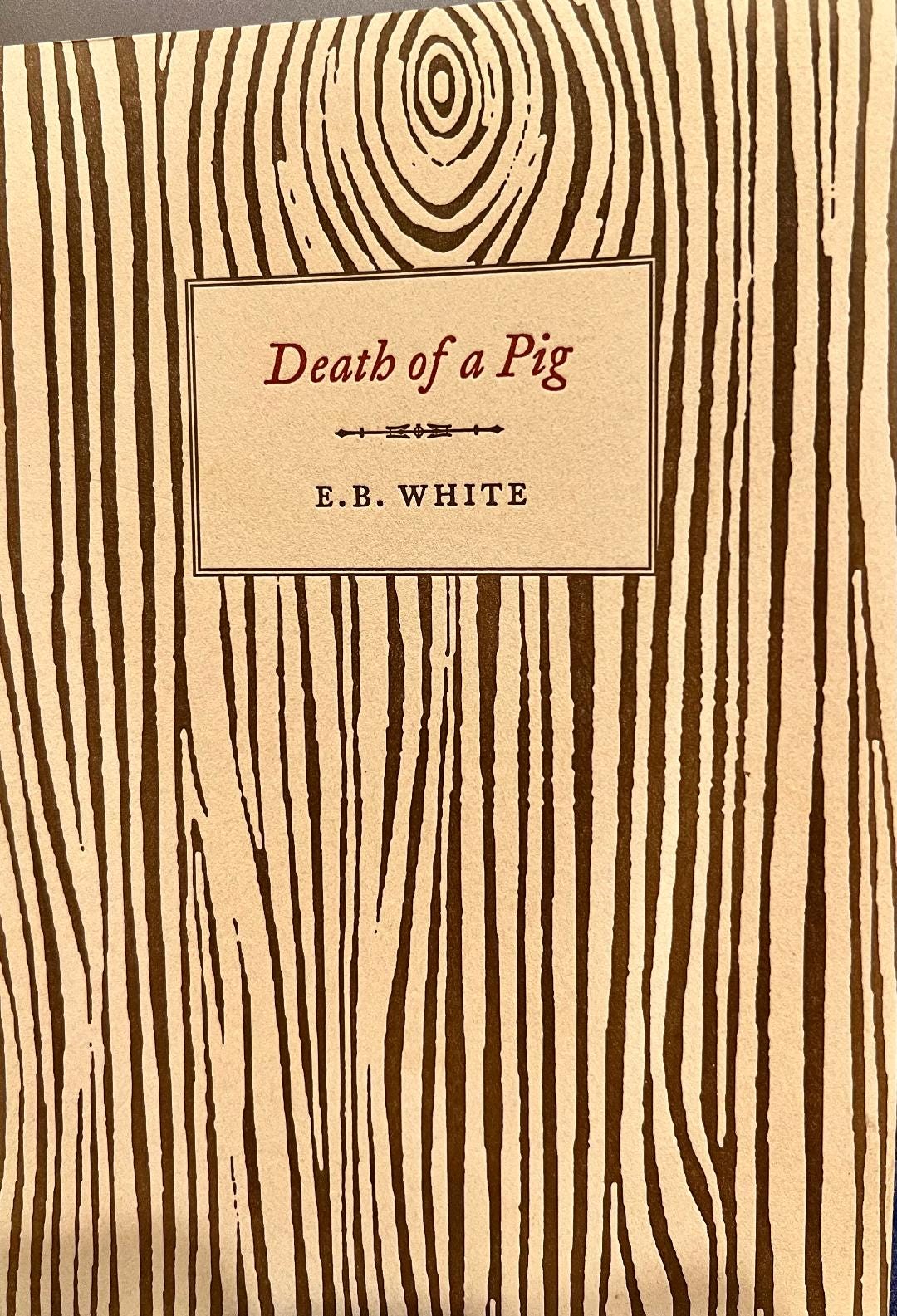

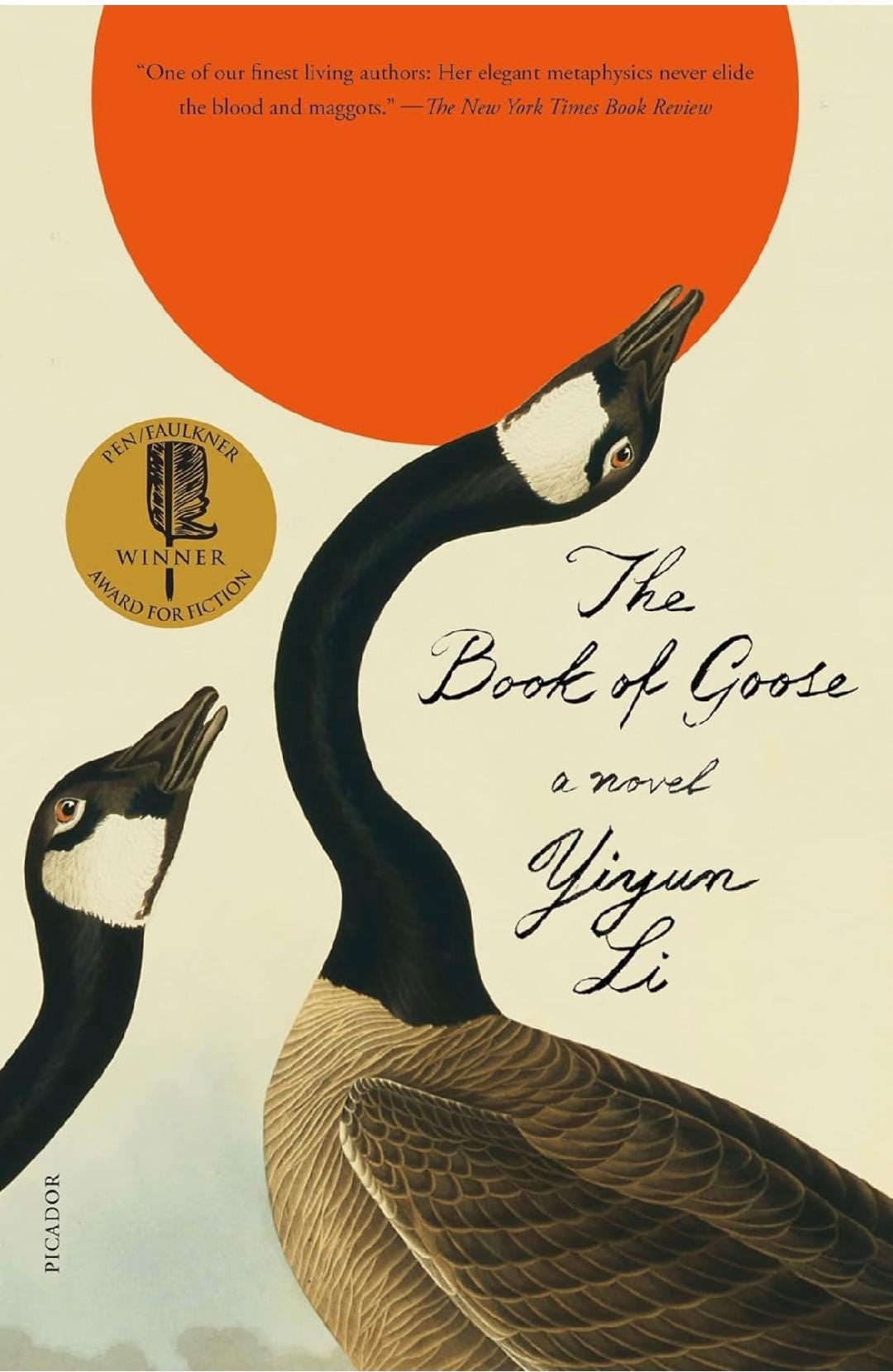

Two books with animals in their titles drew my attention this month: The Book of Goose by Yiyun Lee, winner of this year’s PEN Faulkner Award for Fiction and a reprint of The Death of a Pig by E.B. White, reproduced by Thornwillow Press from whom I receive a monthly gift subscription of small, elegant paperbacks of long-forgotten texts. White’s essay The Death of a Pig is the predecessor to his children’s classic Charlotte’s Web, where Wilbur, the pig, stars as the main character.

Though narrating the deterioration of a pig, White’s engaging prose draws the reader onto the farm and into the pigpen. We know from the title how the story will end, but anyone with a pet can identify with White’s bond to his pig. Though he is raising the pig for eventual slaughter, as its health declines, White’s affection grows.

“I discovered, though, that once having given a pig an enema there is no turning back, no chance of resuming one of life’s more stereotyped roles. The pig’s lot and mine were inextricably bound now, as though the rubber tube were the silver cord,” White writes. “From then until the time of his death I held the pig steadily in the bowl of my mind; the task of trying to deliver him from his misery became a strong obsession. His suffering soon became the embodiment of all earthly wretchedness….”

“It was Saturday morning,” the essay concludes. “…Here, among alders and young hackmatacks, at the foot of the apple tree, Lennie had dug a beautiful hole, five feet long, three feet wide, three feet deep…. As I stood and stared, an enormous earthworm which had been partially exposed by the spade at the bottom dug itself deeper and made a slow withdrawal, seeking even remoter moistures at even lonelier depths. And just as Lennie stepped out and rested his spade against the tree and lit a cigarette, a small green apple separated itself from a branch overhead and fell into the hole. Everything about this last scene seemed overwritten—the dismal sky, the shabby woods, the imminence of rain, the worm (legendary bedfellow of the dead), the apple (conventional garnish of a pig).”

The Death of a Pig foreshadows the story and emotions in Charlotte’s Web where Charlotte, the spider, works her wonder to save Wilbur’s life by weaving the message “Some Pig” and then “Humble” in her web. Charlotte dies soon after.

Yiyan Li’s novel The Book of Goose, narrated in a haunting first person tells the story of Agnès and Fabienne, two childhood friends who grew up as two halves of a not quite whole in Saint Rémy, France. The novel exposes the heart and soul of the girls who are trying to outwit and conquer their everyday lives. Fabienne, the more daring and smarter, but least educated of the two, is constantly inventing games and fantasies for them to live in, including writing a novel as young prodigies then sending Agnes into the world as the celebrated author. In love with her friend, Agnes must find her own way, her own voice and her own will.

The journey includes a stint at a posh, yet tyrannical English boarding school and a flight away from the person others are trying to mould her into and a return to Saint Rémy and Fabienne, who we learn at the start of the book has died. The tone and the writing have a quiet, insistent momentum so that when I finished The Book of Goose, I wanted to read it all over again, to pick up threads and remnants I’d overlooked.

“‘Can you grow happiness?’ I asked…Fabienne said. ‘I have an idea. We grow your happiness as beet and mine as potato. If only one crop fails, we still have the other. We won’t be starved.’

‘What if both fail?’ I asked.

‘We’ll become butchers.’

Such were the conversations we often had then, nonsense to the world, but the world, we already knew was full of nonsense. We might as well amuse ourselves with our own nonsense….”

“…The geese, more than the chickens, are my children. Earl likes the geese, too, and he was the one to suggest that we give them French names….They call me Mother Goose behind my back….Perhaps it is not his fault that I cannot get pregnant. The secrets inside me have not left much space for a fetus to grow….”

“…Somewhere, I believe, somewhere she is laughing. You are still that silly goose, she says. You dream big, Agnes.

But she is wrong about me, just as the world was wrong about us. If my geese ever dream, they alone know that the world will never be allowed even a glimpse of those dreams, and they alone know the world has no right to judge them. I live like my geese.

I have interrupted that living to write; the story of a faux-prodigy, which is the real story of Fabienne and Agnes, as real as on that day when we were in the graveyard, wanting and unable, to kill each other; wanting, and unable to save each other.”

While in London this summer I visited several settings in my latest novel Burning Distance and thought I would continue to share them with you along with passages from the book.

(Over the years I’ve accumulated a running list of words I haven’t known from two main sources: WordDaily and WordGenius)

Gallimaufry

[gale môfre]

Part of speech: noun

1. A confused jumble or medley of things.

2. A dish made from diced or minced meat, especially a hash or ragout.

Examples:

”This is a strange gallimaufry of a book but a fun read.”

“Her room is a glorious gallimaufry of childhood.”

Snollygoster

[snol igg ost ah]

Part of speech: noun

1. A shrewd, unprincipled person, especially a politician

Example:

“Some people think to become successful in the world of politics, one has to be an accomplished snollygoster.”

Petrichor

[petri kôr]

Part of speech: noun

1. A pleasant smell that frequently accompanies the first rain after a long period of warm, dry weather.

Examples:

"I woke up from my nap to the smell of petrichor and the sound of rain coming in from the open window."

"When the air smells of the mineral scent of petrichor, it means it has just rained, or perhaps the rain is coming soon."

I’ve enjoyed giving readings at bookstores, addressing audiences in many venues, and moderating discussions around the world, speaking on a wide range of topics. Click here for a list of past and future speaking events.

Or fill out the speaking request form to schedule an event.

I talk with book clubs and love engaging with readers. If you are in a Reading Group or Book Club and read one of my books, I'd be glad to be in touch by email, zoom, or when possible in person. I can also suggest discussion topics.

Fill out the reading group form here to schedule a meeting.

Great newsletter! Congrats on the forthcoming novel (a new story of international intrigue), and thanks for your observations on the struggle for freedom around the world. I had no idea that Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty had such a huge reporting team. It’s good to know that reliable news is still going to many areas, even as news organizations in general close foreign bureaus. And thanks for keeping a light on imprisoned writers.

Thank you, Julia. And thank you again for your early ideas on content.